In a previous article detailing the rich history of PosiCharge, we focused heavily on this revolutionary technology’s ability to combat dye migration, changing the lives of printers across the country.

Our focus now is on one of the more consistent issues that we see unfolding in screen printing shops from coast to coast, especially during the summer months: the under-cured garment.

Nomadic Apparel

When apparel, bags and caps are manufactured, they’re often subject to extensive travel and rigorous production phases. These raw materials are veritable jet setters that, at times, should almost require a passport for how many different borders they cross.

Building a smooth face fleece? The majority of this piece could be manufactured in Bangladesh, however the zipper pulls need to be applied in Cambodia — the fleece then boards a boat in the Bay of Bengal for its completion prior to the long journey across the Pacific to arrive stateside.

Creating a cotton tee? Cotton may be harvested in India, which is then baled and boarded for a ship destined for Honduras. There it goes through the spinning process and turns into a luxuriously soft ring spun cotton tee, which then boards another boat and makes a weeklong journey across the Caribbean to arrive in the US.

Piecing together performance wear? Synthetic materials, such as polyester, could be spun and built in East Africa, then loaded into a container and shipped on a trans-Atlantic journey where it will arrive at the Port of Jacksonville in several weeks.

What do all of these pieces have in common? They’re all spending weeks on an enormous body of salt water, in a very damp environment with water molecules present in the air.

Many of these garments coming from Central America or Africa then enter the Port of Jacksonville which, depending on the time of year, is typically a very humid point of entry for our traveling companions. This exposes these garments to additional water molecules prior to being cross docked and shipped via truck across our distribution network.

What is often unrealized, and unseen, by a screen print shop is just how much water has been retained within these garments over the course of their journey.

The good news is that, if the garment has retained moisture, it’s getting ready to get released prior to you delivering it to your customer. Unfortunately, there’s a high probability that it will be released under your flash unit, and in your conveyor dryer, which could change the curing dynamic and effect the overall quality of your print.

Like Baking a Cake

If you’ve ever taken a culinary trip through the kitchen and decided to whip up a cake for your family and friends, you’ll likely recall a moment when you turn on the oven light, mid-bake, and wondered “Hmm…it sure looks done.”

Perhaps you even took that cake out of the oven, let it cool for ten minutes, cut into it, and experienced a rapidly spreading pile of goo across your countertop. What looked baked to completion, was only baked on the outside, while the inside was still an oozy mixture of raw egg and flour.

Curing prints on a garment is a lot like baking a cake.

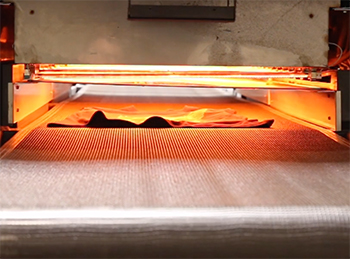

When a printed garment is placed on a conveyor dryer, it enters a chamber where the ideal cure temp for standard plastisol ink on a 100% cotton tee is 320°F. Various inks cure at various thresholds. Many low cure inks can come to a full cure at much lower temps, such as 270°F.

When a printed garment is placed on a conveyor dryer, it enters a chamber where the ideal cure temp for standard plastisol ink on a 100% cotton tee is 320°F. Various inks cure at various thresholds. Many low cure inks can come to a full cure at much lower temps, such as 270°F.

However, ink that may look cured is not always what it seems.

Case in point: the moisture that our traveling garment collected during it’s cross-continental trip may be off-gassing in your conventional dryer. As you place garment after garment after garment into the dryer chamber, the moisture being expelled from the fabric is now creating a humidifying effect and compromising the environment within the chamber itself, thereby preventing your prints from hitting that full cure threshold that we’re looking for.

In this situation, relying on the temperature display is not enough, as the dryer is set to its ideal temperature but unable to account for the environmental factors at play within itself. Even running a donut probe through the dryer during pre-production is not accounting for what is occurring mid-production as moisture is being released.

To top it all off, if your overall shop environment is humid you’re only adding water to a waterfall.

Like the cake that we baked, we need to ensure that the ink hit its full cure threshold from top to bottom, impacting all ink layers – not just the top. It’s not uncommon for a printer to believe that their prints are fully cured, when in fact only the top layer has hit its full cure threshold, while the underlying ink is still uncured. Without being fully bonded to the garment, the ink will crack and fade away as quickly as the first wash cycle at home.

Identifying the Invisible Enemy

Dealing with moisture retention in your garment is challenging, because at first touch we may not feel any dampness at all. It isn’t until the garment is exposed to heat that we start to see just how much water our garments have been holding on to.

It’s paramount that you run an initial test print or two through your dryer and perform a stretch test prior to production. If the ink isn’t fully cured, you’re very likely going to see that ink start to split or crack, especially on synthetic garments, such as polyester. This should be a clear indication that your ink isn’t fully cured.

It’s paramount that you run an initial test print or two through your dryer and perform a stretch test prior to production. If the ink isn’t fully cured, you’re very likely going to see that ink start to split or crack, especially on synthetic garments, such as polyester. This should be a clear indication that your ink isn’t fully cured.

If you still aren’t convinced and you have time on your side, it never hurts to also run several test prints through a wash and dry cycle at home to see how they hold up during a rigorous laundering process. If you see signs of splitting, or even worse, ink degradation, your shirts are most certainly under-cured.

If you happen to have heat press capabilities at your shop, a surefire way to test for moisture retention is by investing in a Teflon sheet. Simply get your heat press up to temperature, place the Teflon sheet over the garment in question, and apply pressure for 10 seconds. Let it cool down and try it again. After two or three test presses, you should start to see the moisture itself building up on the Teflon sheet around the edges of where it contacted the garment. The invisible enemy is now visible, and you know exactly what you’re dealing with.

In the end, it’s important to remember that patience and testing are key when curing prints in your screen printing shop. Even though you may have a large volume run of tees or fleece that need to get rolling immediately, it’s always a best practice to test for moisture in your garment prior to production — especially during summer months.

Due diligence will go a long way towards averting any unwanted surprises for you or your customer. After all, nobody likes their freshly printed tees coming out in the wash.